The plastic continent

— and how to tackle it — may be hogging the headlines, but the shipping

industry – frowned upon as a notorious polluter on a massive scale – is also

being effectively reined in and compelled by law to go green. EU legislation

and the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) are wielding their

increasingly environmental sustainability vision and doing so in a holistic

manner that is impacting shipping worldwide.

Indeed the targeted

spheres are:

- Sea transport of toxic waste

- Dismantling of ships

- Sulphur emissions

In

all fairness, a more environmentally conscious shipping industry has long been

taking shape.

Sea transport of

toxic waste

Spearheaded by the

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the Basel Convention on the

Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal

(Basel Convention), set the ball rolling to mitigate the risks of transporting

toxic waste across the oceans in 1989. Despite expected resistance and taking

three years to be enforced, the ratification of 186 countries provided a step

in the right direction.

The Basel Convention

was aimed at reducing the transfer of hazardous waste from developed to less

developed countries, but not prohibiting them. Thus the Basel Convention relies

on the ‘prior informed consent’ of the authorities of the respective importing

countries to ensure that any hazardous waste is treated in an environmentally

sound manner by the importing countries in question. While environmental issues

began to gain traction, the Basel Convention could not guarantee a foolproof

outcome, more so when 1-off cases were occasionally allowed to bypass the

rules.

An attempt at more

stringent control was adopted in 1995, when the Basel Convention introduced its

‘Ban Amendment’ to prohibit the export of all toxic waste from OECD to non-OECD

countries. Yet, once again, insufficient ratification proved a stumbling block.

Indeed, the Ban amendment will enter into force on December 5, 2019, since

Croatia ratified it on September 6, 2019, being the last ratification required

to meet the three-fourths (of the State Parties to the Basel Convention)

ratification threshold.

The Basel

Convention’s effectiveness in regulating ship recycling began to lose favour,

since its code of practice was not comprehensive enough, particularly as the

adverse impact of climate change started to dominate political agendas.

This goaded the EU to

enforce the Basel Convention, the ‘Amendment Ban’ and the OECD Decision C

(2001)107/FINAL, unilaterally in 2006 through its Regulation (EC) No 1013/2006

on shipments of waste, known as the European Waste Shipment Regulation (WSR). The

WSR includes a ban on the export of hazardous wastes to non-OECD countries, as

well as a ban on the export of waste for disposal. This stipulated that, since

the dismantling of ships was now deemed as ‘hazardous waste’ and as long as the

conditions adopted by the WSR are satisfied, no end-of-life ship leaving any EU

port could be exported to a non-OED country to be scrapped. In fact, the

concept of flag state was once again waived off. The outcome of this regulation

did not prove successful so in order to strengthen Member States’ inspection

systems, WSR was amended in 2014 through Regulation (EU) No 660/2014 of 15 May

2014.

Dismantling

of Ships

The arduous and

hazardous dismantling of old and decommissioned vessels is a nightmare on all

fronts – health & safety, logistical and environmental. More so when

carried out on beaches – a horrifying reality – especially in the Far East. The

complexities involved also need to factor in the skewed size-age distribution

of the world’s fleet, since smaller ships operating in domestic waters weather

much better than large ocean-going vessels that tend to be scrapped at around

25 years of age.

Moving

towards a circular economy, however, has been piling on the pressure for

greener solutions that obviously recognize ship recycling as the best solution

for ships ceasing operations.

In May 2009, the Hong

Kong International Convention (Hong Kong Convention) for the Safe and

Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships brought 63 countries together to

formulate guidelines that would mitigate the operational and environmental

risks involved in the reprocessing and scrapping of ships in the world’s

recycling locations. As a result, the Hong Kong Convention addressed human

health issues vis-a-vis working conditions, particularly workers’ occupational

and safety conditions at the ship recycling facilities (defined areas used for

ship recycling). Basics such as providing workers with adequate protective

equipment and training became mandatory, while a nearby hospital became another

prerequisite.

The complexities in

compiling these guidelines and subsequent compliance were further shackled (and

continue to be shackled) by the entry into force criteria which were bound to:

- a minimum

number of ratifications;

- ratified

states should represent 40% of world merchant shipping by gross tonnage;

- a combined

maximum annual ship recycling volume of the said states should amount to at

least 3% of their combined merchant shipping tonnage during the preceding 10

years.

Four years on, the

European Union entered the fray in the role of champion and reinforcement of

the said Hong Kong Convention. Given its clout of 35% ownership of the global

merchant fleet[1]

and its mission to raise the standards bar, the EU adopted its Regulation on

Ship Recycling at the end of 2013 allowing a 5-year grace period until full

implementation; the regulation is effective from January 2019. From the very

beginning of 2019, a new chapter regarding the recycling of vessels began to be

written.

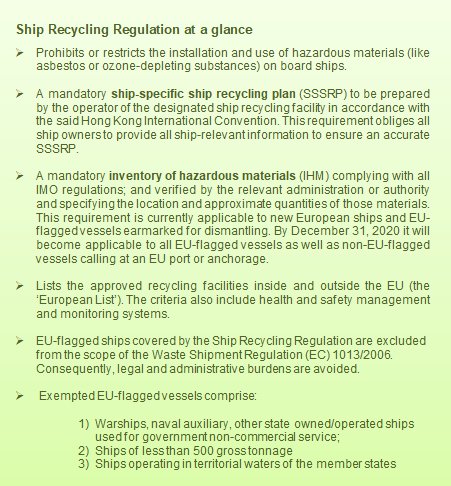

Touted as

“the only legally binding and comprehensive instrument on ship recycling in

force in the world today,” EU Regulation No. 1257/2013 stipulates that all EU-flagged

vessels have to be dismantled according to strict guidelines in one of the

approved European List shipyards. Although most of these yards are located

within the EU, a few are situated in Turkey and the U.S.A. Significantly, the

invitation is open for other shipyards to join the list as long as they meet

the stringent requirements. As for the European List of Authorised Ship

Recycling Facilities, this has been last updated on 17 June 2019 by the Commission’s

Implementing Decision 2019/995 of that date. At the same time, the EU has come

under fire for stalling a number of applications.

Nevertheless, even the most cynical of skeptics cannot

dispute that the EU Regulations are a step in the right direction of

sustainability, especially since no specific global rules on ship recycling

exist. Putting lives and the planet at risk is no longer acceptable. Minimizing

waste and repurposing valuable materials – primarily steel – point to another

two linked priorities. These in turn both reduce the need for mining while

creating a lucrative market buoyed by perpetual recycling.

Any

detractors of the EU’s Ship Recycling Regulation were recently put in place by

the criminal prosecution in Rotterdam of Seatrade in March 2018, after its

directors were found to have breached existing EU regulations by indirectly

selling ships to scrap yards in non-OECD countries. The implications of this

case amply manifest that no ship owner (of any flag) can ‘mis-declare’ its

intended destination when leaving European waters for recycling and hope to get

away with violation of the rules. Even more significantly, resorting to reflag

outside Europe to avoid pertinent regulation will fall under scrutiny to

ascertain that bypassing the rules is not intended.

Sulphur Emissions

No

maritime environmental write-up would be complete without a reference to the

0.5% Sulphur Cap imposed by the IMO for ships operating outside Emission

Control Areas, effective as from January 1, 2020.

The

current Sulphur Cap stands at 3.5%, meaning that the new limit will result in a

drastic reduction in the maritime industry carbon footprint. Regarding

applicability, the 2020 cap will apply to all ships flying the flag of a state

that has ratified MARPOL Annex VI and/or calling at a port or passing through

the waters of a state that has ratified the MARPOL Convention. This will

eventually include a great number of the world’s fleet. The new regulations are already boosting the

production of liquefied natural gas (LNG) and other compliant alternative

bunkers. The option is, however, dependent on the availability of a worldwide

network of LNG bunkering infrastructure.

Shipowners

who will not opt for LNG and would still like to make use of Heavy Fuel Oil

(HFO) should install scrubbers or exhaust gas cleaning systems onboard their

vessels, which is a time-consuming exercise involving a hefty capital outlay

and more structural modifications.

While

environmentalists cheered the news of the revised sulphur cap, several stakeholders

have expressed their doubts, primarily where the use of scrubbers is concerned.

Detractors argue that shifting pollution from the sea to the air is a perfectly

futile exercise. They argue that the onus lies on oil refineries and other

alternative fuel providers to produce eco-gasses in the first place. Meanwhile,

they advocate slow steaming.

Should slow-steaming become

obligatory across the board, the maritime industry is in for a massive

re-think.

What are the immediate implications?

Environmentally speaking, slower speed should reduce carbon

dioxide emissions. The biggest hurdle is

to maintain market driven delivery dates. On the other hand, it is argued that

the proposal would be counterproductive, since it would necessitate an increased

number of vessels at sea to ensure current and future demand expectations. It would even trigger an increased demand for

more vessels to be built, therefore escalating the strain on the environment.

Furthermore, charter markets will cease to operate smoothly, charter and spot

rates will spike resulting in a starker imbalance between the gainers and

losers in the maritime industry.

Conclusion

Today’s realities are

having the shipping industry increasingly embrace environmental sustainability

and, like any other major or minor industry, its future economic viability

depends on adopting eco-friendly policies.

Regarding the

ever-controversial scrapping of ships, the EU Regulation No. 1257/2013

manifests a concerted effort to improve social and environmental conditions

under which ships are dismantled. Yet, even as the EU showcases the busiest of

its ‘green’ recycling yard in Ghent, Belgium, it should be kept in mind that

none of the EU member states could handle the dismantling of large

ocean-crossing vessels. As a result, the success of enforcing the EURegulation No. 1257/2013 depends on

winning over non-EU geographically spread scrap yards that factors in the

issues of which countries are willing to buy ships and which ones are not

reaching full capacity any time soon. Failing to do so would only lead to

reflagging and evasion though, once again, the Seatrade case shows that the EU

means eco-business.

*The

above article had been published on Marine Money Magazine – Legal Issue 2019.

[1] https://ec.europa.eu/environment/waste/ships/