The Shipping Industry is increasingly embracing environmental sustainability

The plastic continent — and how to tackle it — may be hogging the headlines, but the shipping industry – frowned upon as a notorious polluter on a massive scale – is also being effectively reined in and compelled by law to go green. EU legislation and the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) are wielding their increasingly environmental sustainability vision and doing so in a holistic manner that is impacting shipping worldwide.

Indeed the targeted spheres are:

- Sea transport of toxic waste

- Dismantling of ships

- Sulphur emissions

In all fairness, a more environmentally conscious shipping industry has long been taking shape.

Sea transport of toxic waste

Spearheaded by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal (Basel Convention), set the ball rolling to mitigate the risks of transporting toxic waste across the oceans in 1989. Despite expected resistance and taking three years to be enforced, the ratification of 186 countries provided a step in the right direction.

The Basel Convention was aimed at reducing the transfer of hazardous waste from developed to less developed countries, but not prohibiting them. Thus the Basel Convention relies on the ‘prior informed consent’ of the authorities of the respective importing countries to ensure that any hazardous waste is treated in an environmentally sound manner by the importing countries in question. While environmental issues began to gain traction, the Basel Convention could not guarantee a foolproof outcome, more so when 1-off cases were occasionally allowed to bypass the rules.

An attempt at more stringent control was adopted in 1995, when the Basel Convention introduced its ‘Ban Amendment’ to prohibit the export of all toxic waste from OECD to non-OECD countries. Yet, once again, insufficient ratification proved a stumbling block. Indeed, the Ban amendment will enter into force on December 5, 2019, since Croatia ratified it on September 6, 2019, being the last ratification required to meet the three-fourths (of the State Parties to the Basel Convention) ratification threshold.

The Basel Convention’s effectiveness in regulating ship recycling began to lose favour, since its code of practice was not comprehensive enough, particularly as the adverse impact of climate change started to dominate political agendas.

This goaded the EU to enforce the Basel Convention, the ‘Amendment Ban’ and the OECD Decision C (2001)107/FINAL, unilaterally in 2006 through its Regulation (EC) No 1013/2006 on shipments of waste, known as the European Waste Shipment Regulation (WSR). The WSR includes a ban on the export of hazardous wastes to non-OECD countries, as well as a ban on the export of waste for disposal. This stipulated that, since the dismantling of ships was now deemed as ‘hazardous waste’ and as long as the conditions adopted by the WSR are satisfied, no end-of-life ship leaving any EU port could be exported to a non-OED country to be scrapped. In fact, the concept of flag state was once again waived off. The outcome of this regulation did not prove successful so in order to strengthen Member States’ inspection systems, WSR was amended in 2014 through Regulation (EU) No 660/2014 of 15 May 2014.

Dismantling of Ships

The arduous and hazardous dismantling of old and decommissioned vessels is a nightmare on all fronts – health & safety, logistical and environmental. More so when carried out on beaches – a horrifying reality – especially in the Far East. The complexities involved also need to factor in the skewed size-age distribution of the world’s fleet, since smaller ships operating in domestic waters weather much better than large ocean-going vessels that tend to be scrapped at around 25 years of age.

Moving towards a circular economy, however, has been piling on the pressure for greener solutions that obviously recognize ship recycling as the best solution for ships ceasing operations.

In May 2009, the Hong Kong International Convention (Hong Kong Convention) for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships brought 63 countries together to formulate guidelines that would mitigate the operational and environmental risks involved in the reprocessing and scrapping of ships in the world’s recycling locations. As a result, the Hong Kong Convention addressed human health issues vis-a-vis working conditions, particularly workers’ occupational and safety conditions at the ship recycling facilities (defined areas used for ship recycling). Basics such as providing workers with adequate protective equipment and training became mandatory, while a nearby hospital became another prerequisite.

The complexities in compiling these guidelines and subsequent compliance were further shackled (and continue to be shackled) by the entry into force criteria which were bound to:

- a minimum number of ratifications;

- ratified states should represent 40% of world merchant shipping by gross tonnage;

- a combined maximum annual ship recycling volume of the said states should amount to at least 3% of their combined merchant shipping tonnage during the preceding 10 years.

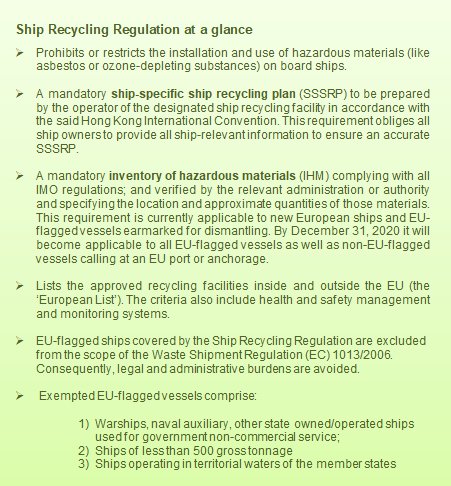

Four years on, the European Union entered the fray in the role of champion and reinforcement of the said Hong Kong Convention. Given its clout of 35% ownership of the global merchant fleet[1] and its mission to raise the standards bar, the EU adopted its Regulation on Ship Recycling at the end of 2013 allowing a 5-year grace period until full implementation; the regulation is effective from January 2019. From the very beginning of 2019, a new chapter regarding the recycling of vessels began to be written.

Touted as “the only legally binding and comprehensive instrument on ship recycling in force in the world today,” EU Regulation No. 1257/2013 stipulates that all EU-flagged vessels have to be dismantled according to strict guidelines in one of the approved European List shipyards. Although most of these yards are located within the EU, a few are situated in Turkey and the U.S.A. Significantly, the invitation is open for other shipyards to join the list as long as they meet the stringent requirements. As for the European List of Authorised Ship Recycling Facilities, this has been last updated on 17 June 2019 by the Commission’s Implementing Decision 2019/995 of that date. At the same time, the EU has come under fire for stalling a number of applications.

Nevertheless, even the most cynical of skeptics cannot dispute that the EU Regulations are a step in the right direction of sustainability, especially since no specific global rules on ship recycling exist. Putting lives and the planet at risk is no longer acceptable. Minimizing waste and repurposing valuable materials – primarily steel – point to another two linked priorities. These in turn both reduce the need for mining while creating a lucrative market buoyed by perpetual recycling.

Any detractors of the EU’s Ship Recycling Regulation were recently put in place by the criminal prosecution in Rotterdam of Seatrade in March 2018, after its directors were found to have breached existing EU regulations by indirectly selling ships to scrap yards in non-OECD countries. The implications of this case amply manifest that no ship owner (of any flag) can ‘mis-declare’ its intended destination when leaving European waters for recycling and hope to get away with violation of the rules. Even more significantly, resorting to reflag outside Europe to avoid pertinent regulation will fall under scrutiny to ascertain that bypassing the rules is not intended.

Sulphur Emissions

No maritime environmental write-up would be complete without a reference to the 0.5% Sulphur Cap imposed by the IMO for ships operating outside Emission Control Areas, effective as from January 1, 2020.

The current Sulphur Cap stands at 3.5%, meaning that the new limit will result in a drastic reduction in the maritime industry carbon footprint. Regarding applicability, the 2020 cap will apply to all ships flying the flag of a state that has ratified MARPOL Annex VI and/or calling at a port or passing through the waters of a state that has ratified the MARPOL Convention. This will eventually include a great number of the world’s fleet. The new regulations are already boosting the production of liquefied natural gas (LNG) and other compliant alternative bunkers. The option is, however, dependent on the availability of a worldwide network of LNG bunkering infrastructure.

Shipowners who will not opt for LNG and would still like to make use of Heavy Fuel Oil (HFO) should install scrubbers or exhaust gas cleaning systems onboard their vessels, which is a time-consuming exercise involving a hefty capital outlay and more structural modifications.

While environmentalists cheered the news of the revised sulphur cap, several stakeholders have expressed their doubts, primarily where the use of scrubbers is concerned. Detractors argue that shifting pollution from the sea to the air is a perfectly futile exercise. They argue that the onus lies on oil refineries and other alternative fuel providers to produce eco-gasses in the first place. Meanwhile, they advocate slow steaming.

Should slow-steaming become obligatory across the board, the maritime industry is in for a massive re-think.

What are the immediate implications?

Environmentally speaking, slower speed should reduce carbon dioxide emissions. The biggest hurdle is to maintain market driven delivery dates. On the other hand, it is argued that the proposal would be counterproductive, since it would necessitate an increased number of vessels at sea to ensure current and future demand expectations. It would even trigger an increased demand for more vessels to be built, therefore escalating the strain on the environment. Furthermore, charter markets will cease to operate smoothly, charter and spot rates will spike resulting in a starker imbalance between the gainers and losers in the maritime industry.

Conclusion

Today’s realities are having the shipping industry increasingly embrace environmental sustainability and, like any other major or minor industry, its future economic viability depends on adopting eco-friendly policies.

Regarding the ever-controversial scrapping of ships, the EU Regulation No. 1257/2013 manifests a concerted effort to improve social and environmental conditions under which ships are dismantled. Yet, even as the EU showcases the busiest of its ‘green’ recycling yard in Ghent, Belgium, it should be kept in mind that none of the EU member states could handle the dismantling of large ocean-crossing vessels. As a result, the success of enforcing the EURegulation No. 1257/2013 depends on winning over non-EU geographically spread scrap yards that factors in the issues of which countries are willing to buy ships and which ones are not reaching full capacity any time soon. Failing to do so would only lead to reflagging and evasion though, once again, the Seatrade case shows that the EU means eco-business.

*The

above article had been published on Marine Money Magazine – Legal Issue 2019.

[1] https://ec.europa.eu/environment/waste/ships/